More Than an Iceberg: 10 Hidden Causes of the Titanic Disaster -- #9 Is Deeply Disturbing

The Titanic sank over a century ago, killing 1,500. Beyond the iceberg, multiple factors worsened the tragedy. Here are 10 lesser-known reasons the disaster was so terrible.

10. Calm Waters

It may sound illogical, but calm seas can be more perilous than stormy ones. On April 14, 1912, the Titanic sailed through a clear, still night—described by a survivor as "perfect serenity." The water was so smooth that plankton produced no luminescence, which would normally have illuminated the iceberg from a distance.

With no waves and a deceptive sense of security, lookouts were less vigilant, and the ship maintained high speed despite the darkness. In clear conditions, icebergs were typically visible 1–3 nautical miles away, but that night, the calm water obscured the hazard until it was too late.

9. Portholes

Most passengers were asleep when the Titanic shuddered after striking an iceberg at 11:40 p.m. Awakened abruptly, many grew curious about the impact and why the ship had stopped. They opened portholes to look out and often left them open when heading to the decks to escape.

Most passengers were asleep when the Titanic shuddered after striking an iceberg at 11:40 p.m. Awakened abruptly, many grew curious about the impact and why the ship had stopped. They opened portholes to look out and often left them open when heading to the decks to escape.

These open portholes allowed water to flood in much more rapidly, significantly accelerating the sinking. Expert Tim Maltin notes that even just 12 open portholes would have doubled the flooding—and with hundreds of portholes and many curious passengers, the actual number was likely far higher, hastening the disaster.

8. Weak Rivets

Today, ship hulls are welded with torches, but in 1912, steel plates like those on the Titanic were joined by hand-hammered rivets. Metallurgists Tim Foecke and Jennifer Hooper McCarthy discovered the materials used were extremely low-grade—far more dangerous than those in typical luxury liners of the era.

Today, ship hulls are welded with torches, but in 1912, steel plates like those on the Titanic were joined by hand-hammered rivets. Metallurgists Tim Foecke and Jennifer Hooper McCarthy discovered the materials used were extremely low-grade—far more dangerous than those in typical luxury liners of the era.

While the exact cause remains uncertain, a shortage of higher-grade rivets or last-minute equipment issues likely contributed. Foecke and McCarthy note that these substandard rivets would have torn apart much more easily than the intended ones.

7. A Typo

On the morning of the Titanic’s sinking, Captain Edward Smith received and acted on multiple ice warnings. Yet, throughout April 14, nine more messages arrived. Among them, a critical warning from the liner Mesaba never reached the captain. Its operator mistakenly typed "MXG" instead of "MSG" – a code requiring the captain's signature – and described severe ice directly in the Titanic's path.

On the morning of the Titanic’s sinking, Captain Edward Smith received and acted on multiple ice warnings. Yet, throughout April 14, nine more messages arrived. Among them, a critical warning from the liner Mesaba never reached the captain. Its operator mistakenly typed "MXG" instead of "MSG" – a code requiring the captain's signature – and described severe ice directly in the Titanic's path.

Overwhelmed by passenger telegrams, Titanic wireless officer Jack Phillips dismissed the mislabeled Mesaba warning. Had its precise ice location been relayed to Smith, the tragedy could likely have been avoided. This fatal oversight occurred amidst a flood of messages that fateful night.

6. Last-Minute Order

Shortly before impact, Officer Murdoch ordered the engines reversed in a desperate effort to avert collision. This stopped the propellers, including the central steering propeller. Scientist Richard Corfield notes this action severely reduced the ship's turning ability.

Shortly before impact, Officer Murdoch ordered the engines reversed in a desperate effort to avert collision. This stopped the propellers, including the central steering propeller. Scientist Richard Corfield notes this action severely reduced the ship's turning ability.

Tragically, Corfield suggests the Titanic might have missed the iceberg entirely if Murdoch had not reduced and reversed thrust. Thus, the emergency maneuver, intended to save the ship, may have instead sealed its fate.

5. No Binoculars

If only the iceberg had been easier to see. The lookout lacked binoculars because crew member David Blair, reassigned at the last minute, accidentally kept the keys, locking them away. Lookout Frederick Fleet later testified that with binoculars, he could have spotted the iceberg sooner—perhaps "enough to get out of the way."

If only the iceberg had been easier to see. The lookout lacked binoculars because crew member David Blair, reassigned at the last minute, accidentally kept the keys, locking them away. Lookout Frederick Fleet later testified that with binoculars, he could have spotted the iceberg sooner—perhaps "enough to get out of the way."

Despite Fleet’s claim, official investigations concluded that the missing binoculars were not a major factor in the disaster. Other critical elements, such as visibility conditions and the failure of nearby ships like the SS Californian to respond, played larger roles in the tragedy.

4. “Shut Up”

Jack Phillips, the Titanic's wireless officer, held a tragically unfortunate role. Many speculate the disaster was exacerbated because he failed to relay crucial ice warnings to Captain Smith. A key example occurred at 22:55 when the nearby SS Californian reported being surrounded by ice. Phillips brusquely told them to "Keep out; shut up," as their loud signal was interfering with his passenger messages from Cape Race.

Jack Phillips, the Titanic's wireless officer, held a tragically unfortunate role. Many speculate the disaster was exacerbated because he failed to relay crucial ice warnings to Captain Smith. A key example occurred at 22:55 when the nearby SS Californian reported being surrounded by ice. Phillips brusquely told them to "Keep out; shut up," as their loud signal was interfering with his passenger messages from Cape Race.

This outburst had severe consequences. Not only was a vital warning ignored, but in his annoyance, Phillips also turned off the radio. This delay later hindered the Titanic's distress signals after striking the iceberg, costing precious time as the ship sank.

3. Speed

Most Titanic experts agree the ship was traveling too fast when it struck the iceberg on April 14, 1912, but disagree on the reason. One theory suggests Captain Smith aimed to beat a transatlantic record or, under pressure from White Star Line director Bruce Ismay, rushed to avoid a late arrival. The ship was at 22 knots, near its top speed, when the collision occurred.

Most Titanic experts agree the ship was traveling too fast when it struck the iceberg on April 14, 1912, but disagree on the reason. One theory suggests Captain Smith aimed to beat a transatlantic record or, under pressure from White Star Line director Bruce Ismay, rushed to avoid a late arrival. The ship was at 22 knots, near its top speed, when the collision occurred.

In Captain Smith's defense, maritime practice at the time encouraged crossing dangerous zones quickly to minimize exposure. However, it is undeniable that had the Titanic been sailing slower, the damage from the iceberg would have been far less severe.

2. Coal Fire

Sailing on a ship that recently had a fire may seem alarming, but in 1912, coal fires were common on steamships due to spontaneous combustion. Therefore, when a fire started in one of Titanic’s coal bunkers on April 13, it was not initially considered serious.

Sailing on a ship that recently had a fire may seem alarming, but in 1912, coal fires were common on steamships due to spontaneous combustion. Therefore, when a fire started in one of Titanic’s coal bunkers on April 13, it was not initially considered serious.

However, later investigations suggested the fire could have weakened the hull, as the bunker was positioned directly against it. Although raised in the original 1912 inquiry—which cited British officials' findings—the theory was not pursued. Historian Senan Moloney believes the presiding judge, possibly influenced by shipping interests, may have avoided it to protect Ireland’s commerce.

1. Ignored Distress Calls

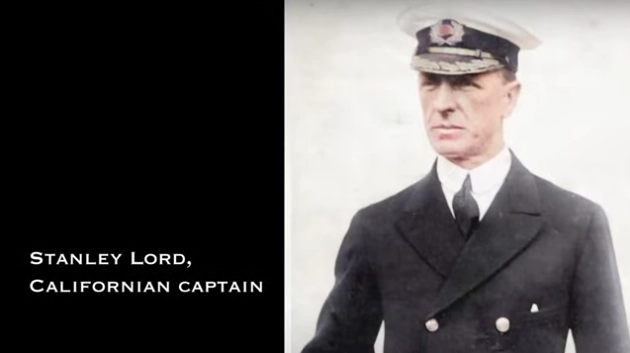

Captain Edward Smith of the Titanic is immortalized as a noble hero who chose to go down with his ship. His sacrifice is celebrated in countless stories and memorials. In stark contrast, Captain Stanley Lord of the SS Californian, the nearest ship to the Titanic, is remembered for his fatal inaction.

Captain Edward Smith of the Titanic is immortalized as a noble hero who chose to go down with his ship. His sacrifice is celebrated in countless stories and memorials. In stark contrast, Captain Stanley Lord of the SS Californian, the nearest ship to the Titanic, is remembered for his fatal inaction.

Awoken when his crew reported distress flares, the exhausted Lord dismissed them as mere "company rockets." His decision to ignore the Titanic's signals meant the Californian failed to assist during the disaster. This neglect doomed many and haunted Lord forever, leading to his disgrace and dismissal.

Leave a Comment